Flying South 2 - October 1999

This is G4FRN with the UK maritime mobile net, standing by.

Mike zero, alpha quebec juliett, emm-emm.

I have a couple of callers. I'll take M0AQJ first. Good morning, Nigel. Greetings to Nicky. How are things with you? I hope you're well. Back to you. M0AQJ/MM from G4FRN.

|

CHART

BOX |

|

Sketch Maps and Chartlets (not to be used for navigation!)

© Copyright 1999 Nigel Jones/MistWeb Software |

Good Morning, Bill, from M0AQJ/MM. Yes, thank-you, all is well on board after a bit of a rough night. We are at three-seven degrees, five-seven minutes north, zero-nine degrees, five-three minutes west. The wind here is still southerly and it's been up to about a force five during the night. The barometer's one-zero-one-one and the wind is down to force four at the moment. We hope you have some good news for us. G4FRN this is M0AQJ/MM.

From G4FRN. I have M0AQJ at 37° 57' N, 09° 53' W. Both crew are well on board, their wind is southerly force 4, pressure 1011 millibars. Well, Nigel, according to Hamburg this morning... let me see... Yes, the wind should go round to the north-west then veer into the north-east during the day. By 1200 they are saying north 5 with gusts to force 7 and two-metre seas. For 1800-zulu it says north-east 4 to 5 for your area. How's that for you? From G4FRN.

That's fine, Bill, thank you. Once we get the wind behind us, everything will seem much better. Thanks for that. We'll let you get on, speak to you again tomorrow. Golf four, foxtrot romeo november, this is mike zero, alpha quebec juliett, mike mike, off and clear. Seven-threes, Bill.

Ok, fine, thank you, Nigel. Now the other caller, this is G4FRN with the UK Maritime Mobile net, please try again...

|

|

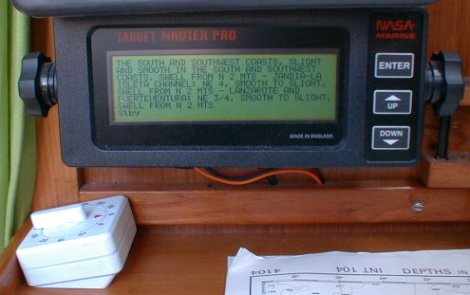

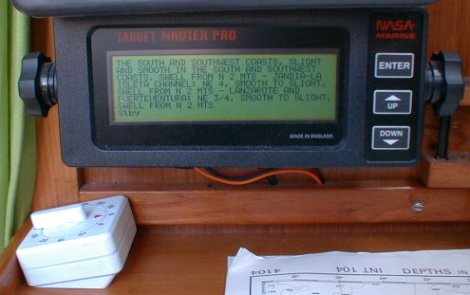

In this photo you can read the screen of the Navtex receiver showing one of the forecasts we used during this passage. Also there is the oven timer which we use on passage and the charts on the chart table - all our essentials!

|

Lisbon to Canaries

Amateur Radio

The stalwarts of the amateur radio marine call-in networks - or 'nets' - have been our daily contact with the outside world during all our off-shore work on this trip. I was advised by Kevin Seymour, who designed the Vancouver 28 (Click here for that story), that once I had the boat there were two more things I needed before setting off: an RYA Yachtmaster Offshore certificate and a full Amateur Radio licence. I took his advice, and he was absolutely right. Click here for details of our radio installations on board. The amateur nets offer a friendly voice to break the sense of isolation, personalised weather forecasts and any amount of other help if matters became at all dire. Bill, Bruce (G4YZH), Tony (G0IAD) and others are on air on 14.303 MHz HF (Short-wave) every day at 0800 and 1800 UTC. They are all ex and current long-distance sailors themselves and provide this invaluable service for other sailing radio amateurs absolutely free of charge and for no remuneration.

|

|

One of the beautiful sunsets from later in the trip. Those clouds in a clear, blue sky are typical of the trade-wind belt, we're told. We watched this one carefully for the fabled green flash, but had no luck.

|

Point of Departure

We had left Cascais, Portugal on a windless day at 1240 local time on Wednesday the 29th September 1999. We motored out to sea with just the mainsail up, dodging all the floating litter and plastic bottles which adorn Portuguese coastal waters. The problem is that the Portuguese use empty plastic bottles as fishing floats too, so some of these were surrounded by enough cheap, floating string to tangle the prop-shaft and ruin our first day at sea. You can never be sure until you're right on top of them, so we tried to dodge every piece of flotsam - quite a task!

When the wind filled in, it was from the south and right on our nose. By the time I called Bill that morning we were more than 7 miles off course as we had killed the engine and had been beating into the stuff for 18 hours. Sure enough, the wind did go round to the north. We kept the reef in the mainsail and ran steadily before a healthy force 4 to 5 for the next three and a half days, making between three and five knots throughout each day and night.

|

|

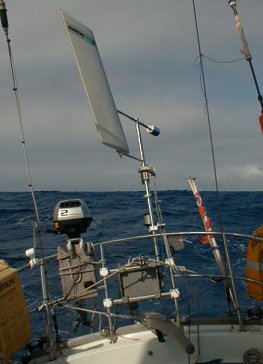

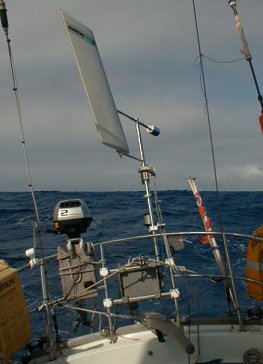

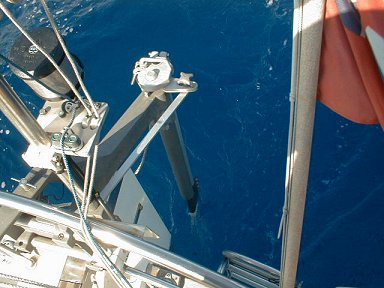

The windvane steered us downwind faithfully for the whole trip. Because we were using the mainsail, you can see that I've set us just off the dead run. This meant we had to gybe about once a day during the trip.

|

Light and Power

The only issue on our minds during that time involved lights and electrical power. The day before we left I had finally made the effort to have a look at our batteries and top up the electrolyte levels in each. We have three large truck batteries on board, one is reserved exclusively for starting the engine and the other two run everything else. These two are charged along with the other when the engine is running, and also receive current from the solar panels during the day. The lead plates were not exposed but all the batteries were thirsty and I managed to fit nearly 2½ litres of de-ionised water into the three of them.

Tri-Colour

Having also fiddled with the masthead tri-colour light in harbour in Cascais we were happy to use it on the first night out. The masthead light is a relatively recent concession to sailing yachts under maritime law. Using only one 25-watt bulb we can show a light with powerful red, green and white sectors as required by the law. It is at a substantial height above the waves where it stands most chance of being seen in the open sea. I had also replaced our old, 10-watt, pulpit-height lights in Cascais. We had two more 25 watt lamps here now, one showing red and green forward, the other showing white aft.

Half way through our first night out that masthead tri-colour went out and it has not worked since. Maybe this time the bulb has simply blown. I should have replaced it when I was up there before. I must get up there again soon...

|

|

This is me attaching the new boom preventer early on in my procedure for gybing. This line runs all the way to the bow, through a snatch-block and then back to the cockpit for tightening. It is to keep the boom safely out when running - whatever the wind and sea may do.

|

Problems

No problem, I thought. Switch on the low ones, they're just as bright. Not one, not two, but three problems:

- All that powerful light at deck-height found innumerable new ways to reflect back, dazzle us and destroy our night vision.

- When you see these lights in the context of open-sea trade-wind swells, you realise that they are not going to be visible very often over the wave-tops. Waves ahead of the boat were brightly lit red and green, while those behind had all the foam picked out in white.

- They use twice as much power as a single 25 W bulb.

By the small hours of our second night, the GPS was making funny alarm noises and, investigating, I found our main battery voltage was down to 8.5 volts from its usual 12 V - the lowest I have ever seen it. I started the engine and switched off all non-essentials. We had navigation lights and the GPS only, no wind or boat-speed instruments, no compass light, no red interior lighting, no chart-table light, no radar, no fridge, no VHF radio monitoring calling and emergency channel 16, no BBC World Service on the HF.

|

|

Here I am disconnecting the windvane to take manual control of the steering for a gybe. Except in the lightest winds we never go out into the cockpit or on deck without a harness and tether.

|

Towed Generator

We had to get used to it: even with running the engine between 2 and 3 hours a day, we were never going to have all these luxuries again on this trip. I still do not know if the problem was all that fresh water in the batteries without plenty of time for it to charge and acclimatise before we left, the extra 30 watts of nav-light power, the cloudy weather, the possibility that our batteries have reached the end of their life and need replacing or a combination of all of these factors. I have already ordered a new Aqua4Gen towed generator for future trips and am keeping a close eye on the batteries' behaviour here in port.

I have a battery acid hygrometer somewhere and will dig it out soon to see if that throws any light on the situation. Rechargeable battery technology is a complex subject and I am no expert. At the moment, in port in Tenerife, the solar panels are having a daily struggle to push the battery voltage up into the 14-volt-plus area where we are used to seeing it in the past during the day. But then, I am using the computer a lot at the moment... but we're not using the fridge much... Who knows?

|

|

Now I have the tiller in hand as I carefully steer the boat through the gybe. The wind is almost dead aft and will soon fill the mainsail from the other side. If it is unexpected or too violent, a gybe can be a dangerous manoeuvre, both for crew's heads and the for gear.

|

Secondary depression

By the afternoon of Sunday 3rd October we were seeing squalls come up behind us and pass one side of us or the other. We had seen windspeeds over the deck of 28-knots - well into force 7 if you include our 5 or 6 knots downwind speed in the actual total. Before nightfall we pulled the second reef into the main. This turned out not to be difficult without rounding up into the wind and seas, thank goodness. During the evening and throughout the night it rained heavily and the wind stayed up around force 6 to 7. Eventually the forecasts began to accept that this was happening. Finally we learnt that a secondary low had developed at 40°N 36°W connected to a big depression over Scandinavia. This had sent a front across us, which was now disappearing south into Morocco. The seas had been up to 4 meters apparently (13 feet) and there had been gale force 8 winds in our area.

|

|

With the windvane now steering again on the opposite tack, I am letting out the mainsheet and pulling in the preventer to settle the mainsail back out. Look at the colour of that sky!

|

Life for us

Life for us had not seemed that bad. True, the boat had been rolling from 30° one way to 20° the other every few seconds for most of the time. We were feeling 'subdued' from the sea-sickness effect of this motion. We had not eaten much apart from fruit and bottled water, mainly because of the complete frustration of trying to do anything in the galley. You could put nothing down, even for a second, without a very good chance that it would be thrown over or onto the floor. Opening a cupboard exposed you to the serious risk that, if not all, then certainly some of its contents would fly out and cause a big problem for you. Nicky and I eventually developed a system where we could make half-mugs of tea, and even sandwiches, by both of us co-operating to hold one thing and then the next so that nothing got loose. Boiling water must only be poured into cups propped up in the sink, with no hands involved. The risk of a scald is almost 100% if you try to hold the mug. If you needed two hands for an operation - e.g. peeing in my case! - bracing your body firmly enough was almost impossible. The pain of the bruising on both shoulders and hips (not to mention elbows and knees) made you dread the inevitable next lurch as you went to do each little job.

|

|

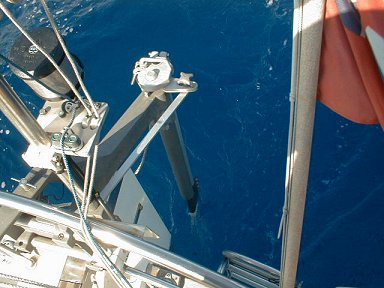

Out here the sea is several kilometers deep. It is a shade of blue that even this photo barely does justice to! This shows the paddle of the windvane steering which provides the power automatically to adjust the rudder and therefore to keep us on course.

|

Following Seas

During the rain, with the wind aft, the companionway had to be kept boarded up and shut to keep the charts, books and electronics dry. We did our watches by sliding back the hatch and poking a head out for a 360° scan every 15 minutes. Even with all this, it was not so bad. It was not cold and no heavy sea water was coming aboard. We were never worried by the situation. Some of the following seas looked a bit steep illuminated by stern nav-light, the water level might reach the gunwhale as they arrived, but we rose easily over all comers.

Sure enough, the front eventually passed during Monday, we saw rainbows and then the sun came out. The solar panels began to do their job again and the sea eventually calmed down. We shook out the second reef and went back to just the first during Tuesday, and eventually re-set first the jib and then the staysail too. Each night we reduced sail to a little below the ideal to be on the safe side. By Wednesday 6th October we were seeing a few passing ships as we got into the area of local traffic between the Canaries and the Madeiras as well as to and from Gibraltar, by the look of their courses.

|

|

It's 0800, Nicky is awake but is she ready to start her watch? Answers on a postcard, please... Notice the white lee-cloth which keeps a body in their bunk during heavy rolling and heeling.

|

Watches

For a long time now, our watch system has been very simple on longer crossings: I have done the nights while Nicky does the days, especially the mornings when I catch up on sleep. In northern, summer waters this has not been so bad for me as the nights are very short, maybe 2300 until 0400 being the hours of true darkness in June in the English Channel - a mere five hours. On this trip, after the equinox, through the 30s-North latitudes, darkness was a full twelve hours, from 2000 to 0800 local (Portuguese and Canaries Summer) time. After a few days I suddenly had a vision of symmetry and perfection, which I shared with Nicky. This is what I suggested: "If I do the noon to 1600 bit of your watch and you do the midnight 'til 0400 bit of mine, I'll be able to cope much better with the 0400 to 0800 bit, having had some proper sleep."

Nicky accepted the deal and did her first ever night watch in the small hours of Wednesday morning. We kept this up for the final three nights of the trip and she is rightly proud of this new achievement in her sailing abilities. What it amounts to is that we are now doing standard 4-hour watches turn and turn about throughout each 24 hours. If we ever introduce the 2-hour dog watches of the afternoon, we shall have the original Royal Navy watch system.

|

|

The sun is about to show over the horizon. The moon has risen above him, but Venus is already way ahead of them both, high in the eastern sky. Another stunning sunrise at sea. (Untouched digital photo!)

|

Clockwork timer

At the moment our actual watches, when out to sea, involve either keeping an eye on the clock or setting a clockwork oven timer so that every fifteen minutes the watchkeeper gets up and does a careful scan of the whole horizon before checking our course on the GPS. After glancing at our speed, the barometer and the Navtex to make sure that the weather is not causing a problem, he or she is free again for another 15 minutes to read or doze before repeating. We did try extending the time to 20 minutes but were alarmed once by how close a freighter had managed to get to us, from being invisible 20 minutes before. This is not too demanding and usually only needs to be changed when a ship is sighted, until the possibility of collision can be ruled out.

Landfall

Having seen some beautiful trade-wind sunsets and sunrises in the last few days, Nicky was treated to our first sight of land when she saw a flashing light ahead in the darkness at 0350 on the morning of Thursday 7th October. By 0430 it was clear enough that I had confirmed, by its flashing pattern and repeat-time, that it was indeed our expected landfall light high in the cliffs of the northern-most tip of the island of Tenerife.

By 0900 the wind had died away to such an extent that we decided to put the engine on to hasten along and guarantee that we would be safe and snug well before dark. At 1530 we entered La Marina del Atlantico, beyond the scruffy, rusty, Russian trawlers lining La Dársena Comercial Los Llamos and right in front of the main square of Santa Cruz de Tenerife. A boat-boy in a marina dory came out to meet us and led us in. He told us that the pontoons were full but that he would find us space. "Two! Good, amigo!" he called, pointing to our two bow-ropes looped back over the pulpit. As we followed him we realised that we were going to be placed bows-to under the sea-wall. He pointed to our anchor, securely lashed down for sea, and called, "This, no!" I was very grateful. Getting all the anchoring gear ready for use at that stage would have been a challenge. The wind had piped up, it was now reaching 20 knots though the harbour, and it was starting to spit with rain from the black clouds pouring down from the mountains behind the town.

|

CHART

BOX |

|

Sketch Maps and Chartlets (not to be used for navigation!)

© Copyright 1999 Nigel Jones/MistWeb Software |

Welcome, amigo

As I nosed Rusalka Mist in towards the wall in the crosswind, Nicky threw him the bow lines (he had ditched the dory and scaled up the wall in what seemed like no time at all!). He passed her a thin line which would lead us back to our stern rope, lying in the mud beneath us. He secured our bow-lines to the quay while I had to winch up the stern line from the mud with a primary sheet winch in the cockpit. Soon we had the boat secure and the boat-boy was noisily and cheerfully welcoming us to the island from the quay, "Iss a lovely island, amigos! You weel enjoy here! A mañana you veesit office! A mañana we do water, electric, whatever you want, ok, amigo? ok! Adios! A mañana!!"

We waved and grinned back, thankful for his welcome and his enthusiasm, grateful too to leave it all for the mañana. We climbed below and put the kettle on, beginning to talk about meatballs for supper...

We have collected lovely pictures of the island and the town. Click here for our edited compilation.